Understanding Alzheimer’s Disease:

A Beginner’s Guide

Stages of Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease unfolds in stages, each with distinct symptoms, and progresses uniquely for every individual. Recognizing these stages and associated symptoms is crucial for timely intervention and effective care.

Stage 1: Preclinical Stage

This early stage occurs years or even decades before noticeable symptoms appear, known as preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. This phase is characterized by changes in the brain, including the accumulation of amyloid protein deposits.

- Symptoms: None; individuals remain asymptomatic and function normally.

- Detection: Advanced brain imaging tests can identify amyloid deposits, but this stage is typically referenced only in research contexts.

- Duration: This stage can last for years or even decades.

Stage 2: Mild or Early Stage

The symptoms become apparent during this stage but are often mistaken for normal aging or stress.

Symptoms:

- Mild forgetfulness, such as difficulty recalling names or recent events.

- Trouble concentrating and organizing tasks.

- Misplacing valuable objects and forgetting their location.

- Struggling with planning or managing finances.

Effect on daily life:

The individual may still live independently but may notice memory lapses. Friends and family may observe subtle changes in behavior.

Stage 3: Moderate or Middle Stage

This is the longest stage of Alzheimer’s disease and typically lasts several years. Cognitive and behavioral symptoms become more pronounced, significantly affecting independence.

Cognitive Symptoms:

- Increased memory loss, including difficulty remembering personal details.

- Trouble learning new information and performing complex tasks, like organizing an event.

- Forgetting familiar names, including those of close relatives.

Behavioral and Emotional Symptoms:

- Mood swings, irritability, or withdrawal from social interactions.

- Changes in personality, such as paranoia (excessive suspicion), delusions (false beliefs unrelated to reality), or hallucinations (perceiving things that are not actually present).

- Anxiety or restlessness, particularly in the late afternoon or night (a phenomenon known as sundowning).

Effect on daily life:

- Difficulty dressing appropriately or managing personal hygiene.

- Frequent disorientation and wandering which can lead to safety concerns.

- Sleep disturbances, such as insomnia or excessive daytime napping.

Stage 4: Severe or Late Stage

In this advanced stage, the individual’s cognitive and physical abilities deteriorate significantly, requiring full-time care.

Cognitive Symptoms:

- Severe memory loss, including unawareness of surroundings or recognition of loved ones.

- Loss of ability to communicate effectively, often relying on nonverbal cues.

Physical Symptoms:

- Difficulty walking, sitting, or swallowing.

- Loss of bowel and bladder control.

- Increased vulnerability to infections, particularly pneumonia.

Effect on daily life:

The individual becomes entirely reliant on caregivers for all daily activities, including eating and personal hygiene.

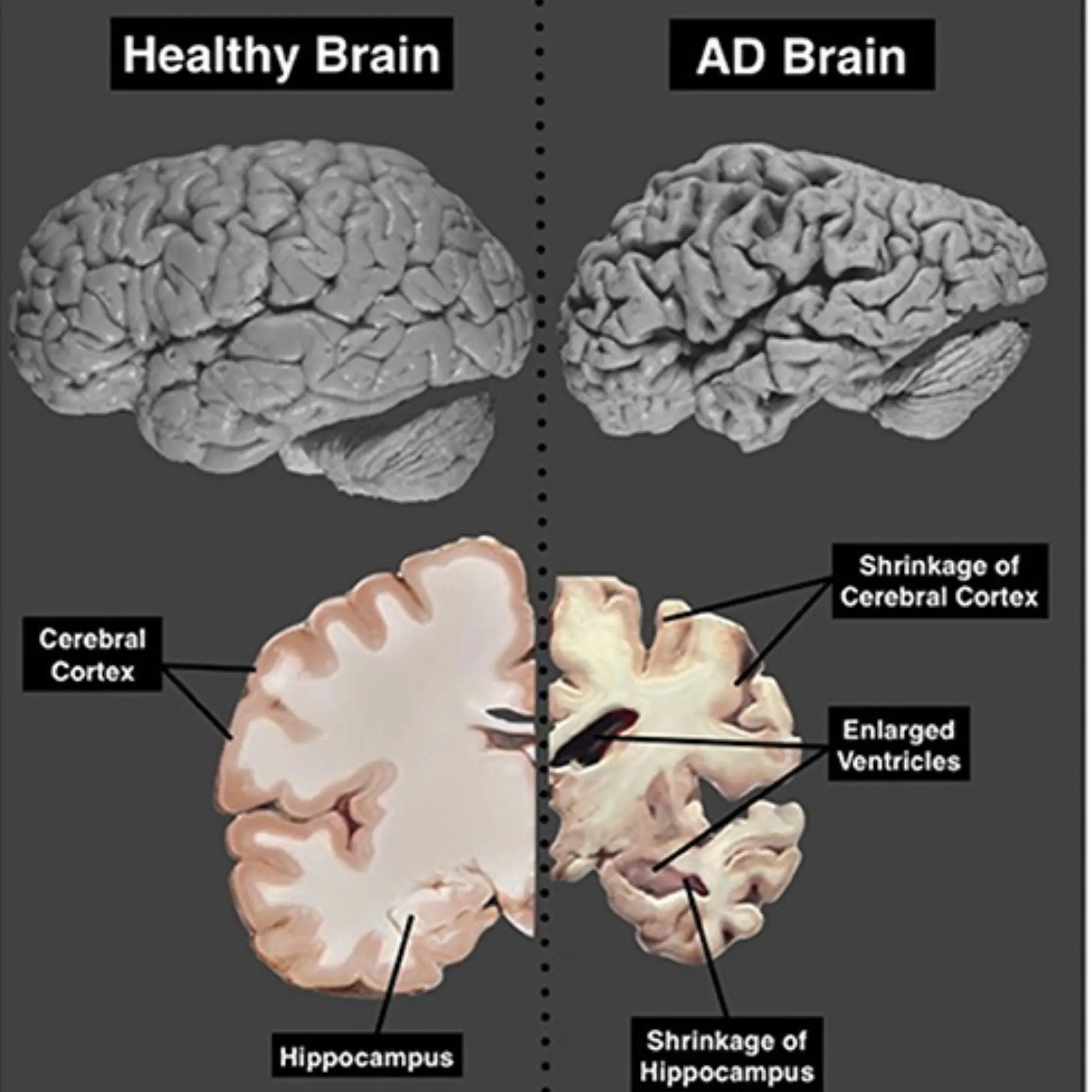

Image representing comparison of brain scans.

Left: Normal brain showing typical structure and volume.

Right: Brain affected by Alzheimer’s disease (AD) displaying significant shrinkage.

Disclaimer: The information provided on this website is based on our best knowledge and has been reviewed by a neurologist. It is intended solely to raise awareness and provide general knowledge about Alzheimer’s disease. This content is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. For personalized guidance and care, please consult a qualified healthcare professional. If you or your loved ones are experiencing symptoms or have concerns related to a neurological disorder, please seek advice from a neurologist.

Preclinical Stage: Subtle Brain Changes without Symptoms

Mr. Mathur, a 65-year-old retired school principal from Jaipur, continued to live an active life, regularly engaging in community discussions and morning walks. Unknown to him, subtle changes were occurring in his brain, with amyloid plaques slowly accumulating. Since he experienced no symptoms, he remained unaware of the disease. However, if he had undergone an advanced PET scan or cerebrospinal fluid test as part of a research study, it might have revealed early Alzheimer’s related changes in his brain.

Mild or Early Stage: Subtle Memory Lapses and Daily Challenges

By the time Mr. Mathur turned 70, he started noticing small memory lapses. He occasionally forgot the names of acquaintances and misplaced household items like his glasses or keys. His wife, Meera, observed that he often repeated questions and had trouble recalling recent conversations. At first, they both dismissed it as normal aging, but when he struggled to manage household finances and forgot appointments, his son insisted to visit a doctor. The neurologist performed cognitive assessments and recommended an MRI, which revealed early signs of Alzheimer’s. While the diagnosis was unsettling, early intervention helped Mr. Mathur adopt lifestyle changes and begin medication to slow down the disease’s progression.

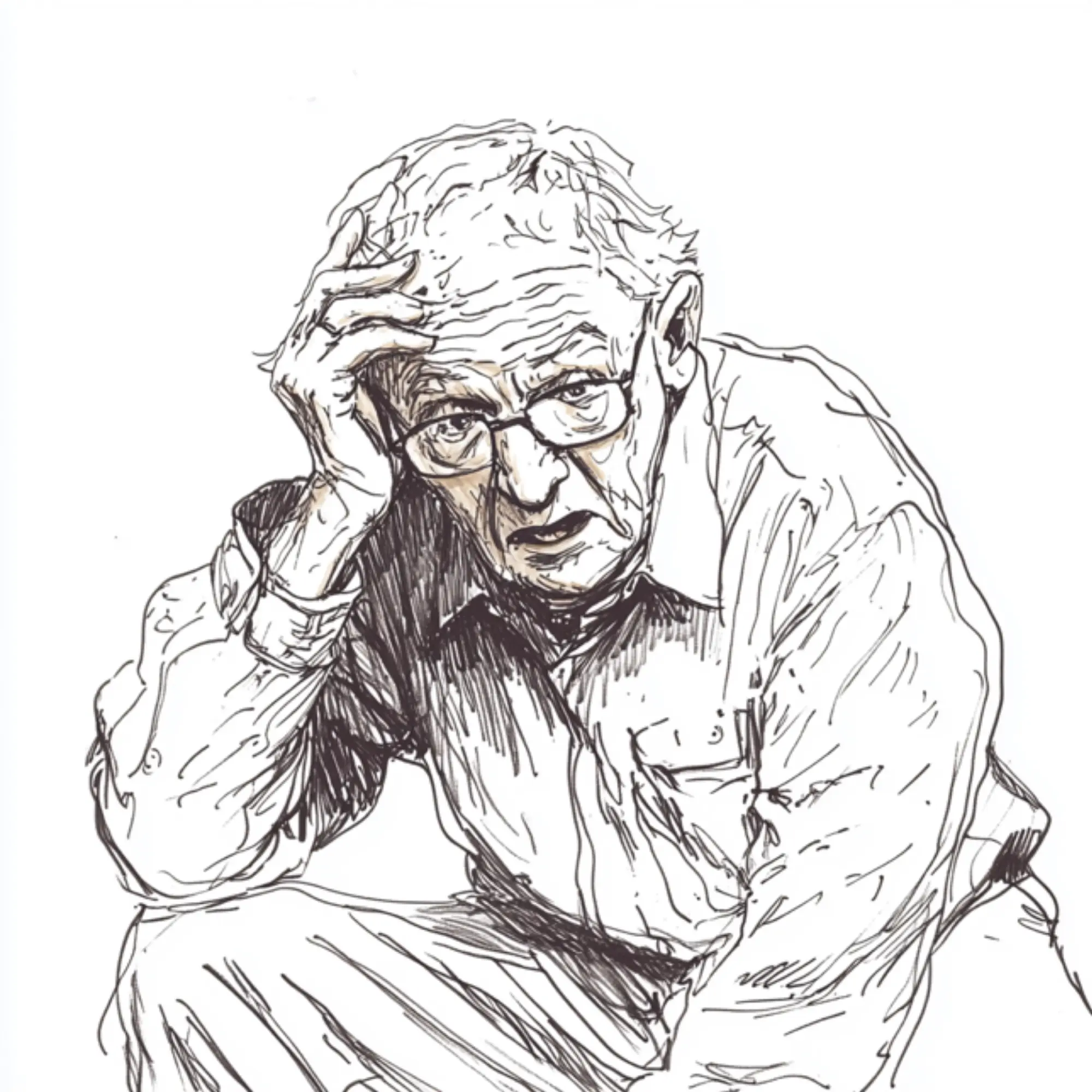

Moderate or Middle Stage: Increased Dependence and Behavioral Changes

At 74, Mr. Mathur’s condition had progressed significantly. He often forgot close relatives’ names and had difficulty following conversations. His once-meticulous daily routines became increasingly chaotic—he sometimes wore mismatched clothes and needed reminders to bathe. More concerning were his mood swings; he became easily frustrated, withdrawn, and at times paranoid, suspecting that his house help was stealing from him. His family noticed that he frequently wandered out of the house, unable to find his way back. They installed safety locks and GPS tracking in his phone to prevent accidents. Despite the challenges, structured routines and emotional support from his family helped manage his condition.

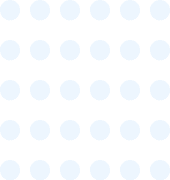

Severe or Late Stage: Full- Time Care and Loss of Independence

By the age of 78, Mr. Mathur had reached the final stage of Alzheimer’s disease. He no longer recognized his wife and children, often staring blankly when they spoke to him. Communication was limited to occasional murmurs and gestures. His physical abilities also declined—he needed assistance with eating, had difficulty walking, and eventually became bedridden. Frequent choking while eating and recurrent infections, including pneumonia, weakened him further. His family, now full-time caregivers, sought professional nursing assistance to ensure he received proper care. Though his condition was irreversible, his loved ones provided him with comfort, dignity, and emotional warmth in his final years.

Disclaimer: This example is just for understanding purposes

Causes and Risk Factors

Alzheimer’s disease is primarily caused by the irreversible damage of neurons in the brain. This gradual destruction of nerve cells begins in the region (hippocampus) of the brain associated with short-term memory, before spreading to other parts of the brain.

The neuronal degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease is linked to changes in two key proteins including amyloid-β and Tau.

a) Amyloid-β

Amyloid-β is a protein naturally present in the brain. The abnormal accumulation of this protein forms clumps in Alzheimer’s disease patients’ brains called amyloid plaques (also known as senile plaques). These clumps are extracellular and toxic to nerve cells, disrupting neuron communication and triggering inflammation that worsens brain damage.

b) Tau

Tau is an intracellular protein that has several functions in the healthy brain, including maintaining the stability of nerve cells. However, in the case of Alzheimer’s disease, Tau protein undergoes abnormal changes and becomes non-functional and forms filaments (neurofibrillary tangles) in patient brain resulting in cell death. Despite extensive research, the exact disease mechanisms of Alzheimer’s disease—remain poorly understood. While several risk factors have been identified and discussed in the following section.

According to the National Institute on Aging (NIA), several factors may increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease:

1. Age and Family History

- Age: The risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease increases significantly with age, especially after 65.

- Family History: If a close family member (biological parent or sibling) has Alzheimer’s disease, your risk increases by 10% to 30%.

- Down syndrome (Trisomy 21): People with trisomy 21 have a higher chance of developing early-onset Alzheimer’s due to the triplication of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene on chromosome 21.

2. Genetic Factors

Several studies suggest that alterations in certain genes are associated with the likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s disease at an early stage (< 65Y) or later stage (> 65Y). The key genes implicated in the Alzheimer’s disease are presenilin, APP, APOE ε4 (apolipoprotein E).

3. Head Injuries

Serious or repeated head injuries, especially around age 55, can raise the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease later in life. Studies showed that moderate-to-severe head trauma may double the risk of dementia. However, not everyone who experiences a head injury will develop Alzheimer’s disease.

4. Gender Differences

Gender is a notable factor, as around two-thirds of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease are women, who are more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease compared to men. This difference is due to a combination of biological and environmental factors, including hormonal changes, genetic predispositions, and differences in life expectancy.

5. Health and Lifestyle Factors

Vascular health issues, such as stroke, diabetes, heart disease, high cholesterol and high blood pressure, are linked to an elevated risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Following a healthy lifestyle- regular physical activity, a balanced diet, cognitive engagement, and social interaction-may help reduce the risk.

- Hypertension: Studies have shown that having high blood pressure in midlife raises the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease later in life. Certain blood pressure medicines like β-blockers, Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and diuretics – may help lower this risk. Lowering midlife hypertension could potentially prevent thousands of Alzheimer’s cases worldwide.

- Diabetes: Studies have shown that Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) is strongly linked to Alzheimer’s disease pathology through multiple interconnected mechanisms. Impaired insulin signaling in the brain leads to neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and abnormal tau phosphorylation, all of which contribute to neurodegeneration.

In T2D, hyperinsulinemia reduces amyloid-β clearance by competitively inhibiting its degradation via insulin-degrading enzyme, thereby promoting amyloid-β accumulation and aggregation into plaques. Emerging evidence suggests that antidiabetic drugs such as metformin, Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, and intranasal insulin may help mitigate Alzheimer’s disease risk by improving insulin sensitivity and reducing neuroinflammatory responses.

6. Immune System Dysfunction

Emerging research suggests that issues with the immune system may also play a role in Alzheimer’s disease development, possibly due to chronic inflammation or the inability to clear toxic protein clumps from the brain.

7. Mild Cognitive Impairment

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) refers to small changes in cognitive ability that do not significantly affect with daily life. While not as severe as Alzheimer’s disease, MCI can be an early indicator of the disease. However, MCI does not always progress to Alzheimer’s disease; in some cases, symptoms may stabilize or even reverse.

Protective Factors

📖 Education

- Education helps people cope better with memory problems, as they often find smart ways to manage daily tasks.

- Studies show that people with more education or mentally stimulating activities may have a lower risk of Alzheimer’s, even if they develop brain changes.

- Staying mentally active through education and hobbies like reading or playing games helps build a “cognitive reserve” that protects the brain.

🏃 Exercise

- Regular physical activity is not just good for the body—it also supports brain health.

- Research shows that older adults who stay active may have better memory and thinking skills, and exercise can even slow brain changes linked to Alzheimer’s.

🍅 Diet

What you eat can affect how your brain ages. Diets high in saturated and trans fats may increase the risk of Alzheimer’s, while healthy fats—like those in fish, nuts, and olive oil—can protect your brain.

Regular fish intake and omega-3 fatty acids are especially helpful. Following a Mediterranean-style diet, which includes plenty of vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins, has been linked to better memory and a lower chance of developing Alzheimer’s. Avoiding heavy alcohol use also helps support brain health.

Smart Aging Strategy

“Never retire in life — stay engaged, stay active. A moving body fuels a thinking brain — regular exercise, a healthy diet, and continuous learning and mental stimulation can slow cognitive decline and help prevent Alzheimer’s disease. Stay active, stay sharp.”

Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease

Previously, definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease was only possible after death by examining the brain under a microscope for protein deposition. Today, advancements in healthcare and research allow professionals to diagnose the disease with greater accuracy while a person is still alive.

Diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease involves a comprehensive assessment to rule out other conditions and identify patterns of cognitive decline. While no single test can confirm Alzheimer’s disease, a combination of tools and evaluations is used to arrive at a diagnosis. A healthcare professional may check the following areas in order to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease:

A healthcare provider may conduct laboratory tests, brain imaging, or comprehensive memory assessments (discussed below) to eliminate other conditions with similar symptoms.

- Physical and neurological examination: To evaluate reflexes, coordination and balance, muscle strength, and sensory responses.

- Mental status (cognitive) testing: Focusing on testing thinking and memory skills. The results of these tests can indicate the severity of cognitive impairment.

- Neuropsychological tests: A neuropsychologist can do extensive tests to determine if the patient has dementia. This will help them know if the patient can safely complete daily tasks, such as taking medicines on time and managing finances.

- Interviews with friends and family: To check for abnormalities in the patient’s behaviour.

- Laboratory tests: To rule out diseases like thyroid conditions, vitamin B-12 deficiency, electrolyte imbalance, infections, autoimmune diseases or metabolic conditions.

- Lumbar Puncture: To measure amyloid-β and tau proteins in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the ratio of which can determine if a patient has Alzheimer’s dementia. However, this is an invasive procedure that requires inserting a needle into the lower back to examine the CSF.

Key Tools and Frameworks

- NIA-AA Diagnostic Criteria: The National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association guidelines are widely used for clinical diagnosis.

- DSM-5 Criteria: The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edition) includes criteria for diagnosing major or mild neurocognitive disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease.

CSF-based test for Alzheimer’s disease:

Antibody-based CSF test has been developed in the US (Roche) for measuring amyloid-β, tau, and phosphorylated tau levels, offering a reliable method for early diagnosis and monitoring of Alzheimer’s disease progression.

Blood test for Alzheimer’s disease:

Several recent studies have highlighted the development of blood tests for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease. A prominent study examined the effectiveness of a blood test called ‘PrecivityAD2. The test measures specific biomarkers associated with Alzheimer’s disease, including amyloid-β and phosphorylated tau. The PrecivityAD2 test demonstrated approximately 90% accuracy in detecting Alzheimer’s disease. The test was recently launched in the US, offering a promising tool for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease; however, it is not yet available in India.

Brain Imaging Tests:

These tests can help rule out other causes of symptoms, such as strokes, heavy bleeding, or brain tumors. They can also help distinguish between different types of neurodegenerative diseases and provide a baseline for the degree of degeneration. The most common brain-imaging technologies include:

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) uses magnets and radio waves to create a detailed view of the brain. An MRI would be able to detect brain shrinkage, particularly in the hippocampus (critical for memory), as well as identify structural abnormalities or vascular damage.

- Computerized Tomography: Computed Tomography (CT) uses X-ray to obtain cross-sectional images of the brain and is useful for detecting strokes, tumors, or head trauma.

- Positron Emission Tomography: Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scan uses a radioactive tracer to identify brain regions with certain signatures. One such radioactive tracer is fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), which can help identify glucose metabolism in different regions of the brain. This pattern of metabolism can help distinguish between different types of neurodegenerative diseases. While Amyloid PET can be used to detect amyloid plaques—a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease— it is important for patients to note that such advanced diagnostic facilities may not be readily available at all healthcare centres.